sola dosis facit venenum

Or: the dose makes the poison

First, two quotes, one in English and one in German.

Don’t worry, we’ll translate the German (this isn’t one of those 19th century novels that expects fluency in English, French, Latin, Italian, and German just to get through a page), and the same basic idea is found in the English quote. In German one of the words has a delightful history that is exposed when juxtaposed with an English translation.

Poisons in small doses are the best medicines; and the best medicines in too large doses are poisonous.

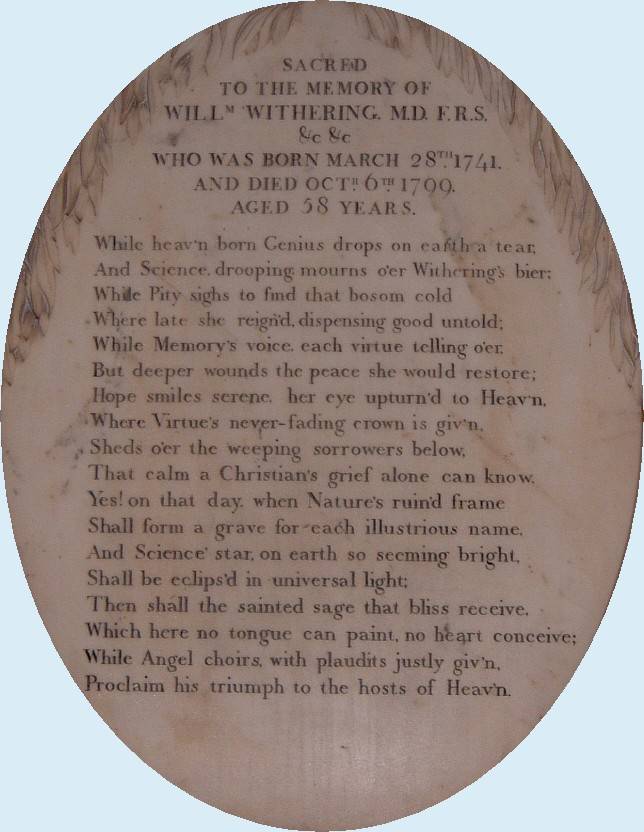

William Withering, 18th century English physician, discoverer of digitalis (sort of), and proponent of arsenic therapy. 1 2

Alle Dinge sind Gift, und nichts ist ohne Gift; allein die dosis machts, daß ein Ding kein Gift sei.

The phrase “sola dosis facit venenum,” (usually rendered “the dose makes the poison” in English) is a Latinization of the German phrase above from Paracelsus. He wrote this in his “Seven Defenses” when he was fighting against accusations of poisoning his patients3 (malpractice court, it seems, is one of the oldest traditions in medicine).

Here’s my rough translation from Paracelsus’ German:

All things are poison, and nothing is not a poison. Only the dose makes the thing not a poison.

Throw in a couple of exclamation marks, italics, and fist pounds, and you have the makings of dialogue for the defendent in a 16th century Law and Order.

Paracelsus

Why did this German guy have a Latin name?

No one really knows. Von Hohenheim’s relationship with Latin and the humanistic antiquity it represented was complicated. Despite writing books with names such as Septem Defensiones, he was known for refusing to lecture in Latin, preferring vernacular German instead, and the content of his books was invariably German.4 He publicly burned old Latin medical texts, along with their outdated ideas. My favorite version of the Paracelsus story is that the Latin name was first given to von Hohenheim by his friends, who were probably screwing with him, as they knew it would go against his iconoclastic bent. He used it (with a glint in his eye) as an occasional pen name, and it eventually stuck.

In this spirit I decided on the Latin slogan. It’s a bit of a post-post-modern jab at myself, medical tradition, and old bearded white men, who sometimes knew how to make fun of themselves and occasionally had good ideas despite their bearded whiteness.5 Also, Latin is pretty. And regardless of language, the idea this phrase represents is possibly my favorite, in medicine and in life.

Poison and other gifts

The word for “poison” in German is Gift. English “gift,” meaning “present,” comes from the same Proto-Indo-European root: ghebh-, “to give.” (Language is, after all, susceptible to divergent evolution, sometimes amusingly). This dual meaning fits nicely with the general conceit — medicine and poison are two sides of the same coin, gifts in either case, to be used with judgment, not to excess.

We can keep going down the etymologic rabbit hole: poison comes from Proto-Indo-European po(i), “to drink,” the same root that gave us “potion” and “potable.” The Latin venenum from our quote, which eventually led to English “venom,” comes from Proto-Indo-European wen, “to desire, strive for,” which made its way around to wenes-no, “love potion,” and then to more general meaning as “drug, medical potion,” before finally assuming the modern meaning of a dangerous substance from an animal. I wonder if the evolution of these words from neutral or positive to negative reflects cycles of hope and disillusionment. The history of medicine is filled with well-meaning, careful clinicians who were often simply wrong, as well as charlatans (medicasters, even).

By contrast, the word “medicine” has undergone remarkably little change in meaning. It comes from Proto-Indo-European med, “to take appropriate measures,” a root shared with “meditate,” “modest,” “accomodate,” and, of course, “commode.” This is a complete way to think about how to practice and receive medicine: to take appropriate measures. The difficult part is deciding what “appropriate” means.

So what?

I’m going to be a doctor shockingly soon (2020, two years after this writing). After residency I will most likely specialize in either hematology-oncology (blood cancer) or palliative care,6 and in either case will help people decide which poison to take in an effort to feel better.

Crazily enough, some of the best treatments for some of the worst diseases are classical poisons, such as arsenic for some leukemias. Arsenic is what the lucky ones get to take — we have and regularly use other drugs that are much more dangerous. It’s not just drugs we poison people with, either. If you are fortunate enough to have the right kind of cancer, enough physical strength left in reserve, and a donor to make you eligible for a bone marrow transplant, get ready to become friends with a linear particle accelerator. We radiate the bone marrow until it gives up the ghost, then start over fresh, resurrection from the inside out.

In palliative care it’s not so different, even though the goal is symptom management and not cure. An illustrative anecdote: during a palliative care rotation I was trying to help the physician do some calculations she had been doing by hand. I thought, “there has to be an online calculator for this…”, and pulled up several medical calculators from respected organizations. In every case, after I put in the drug and dose I wanted, the website would say something like,

“Hell no. We don’t touch that stuff. We’re not even going to do the calculation for you. If you need that medicine at that dose, call a palliative care doc. Consider our asses covered.”

We dispense derivatives of poppy that make heroin look tame, administer amphetamines as antidepressants, and we’re starting to get good at using LSD. Poisons, all. Medicines, all.

My smartass response when people ask me why I chose medicine is “power, drugs, money, and women.” It’s not entirely untrue: nobody else is allowed to use these tools on humans, whether fancy knives or fancy x-rays or fancy poisons; I will always have a job and a comfortable living no matter what happens to the economy (my wife and I have had kids since undergrad, which didn’t change my career goals but added an extra layer of responsibility); and chicks dig docs in uniform (the coat is white because it’s hot).

To sum up:

In the right hands, with respect and care, even the most dangerous substances can be tools for healing. I love that. So, for now at least, the pretentious phrase stays. Once more, with gusto: Sola dosis facit venenum.7

-

Foxglove, the common name for Digitalis purpura, has been used in medicine for centuries, most notably for “dropsy,” the edema (fluid accumulation) associated with heart failure and other conditions. <p> Withering was the one who figured out extraction methods, dosages, and side effects, and most thoroughly estabilshed it as a medicine rather than a folk remedy or poison, but it didn’t come out of nowhere. This is almost always the case: we stand on the shoulders of giants, aspirin comes from bark, etc. </p> <p> While I kind of wish the story that Withering stole it wholecloth from a local herbalist, Mother Hutton, was true, as it would fit my bias that most medicine is built on masculine appropriation of traditionally feminine arts without giving proper credit, this particular story does not appear to have any historical basis. (by the way: amniotomy hooks are sharpened crochet hooks, surgical technique is mostly translated sewing technique, pharmacy is fancy herbalism — and it’s not just in medicine: is a chef a man or a woman? What about a cook? Men make art, women make crafts. Etc., ad nauseum.) ↩

-

The article from The Oncologist that gave us the Withering quote made the unfortunate mistake of saying he was a 15th century physician, which has, even more unfortunately, led to the persistence of the wrong century attached to his name in other publications. He was born in 1741, discovered digitalis in 1775, and died in 1799. <p> </p> Because I’m completely insufferable:

↩

↩ -

If we put on our 21st century lenses, we see that he was indeed poisoning his patients, but in good faith rather than out of quackery or malice. Paracelsus himself probably died from mercury intoxication, incurred from years of practicing alchemy, which was a perfectly respectable occupation for the learned of the time. ↩

-

One of the richest records of Paracelsus’ thought is The Basle Lectures, which is written in Latin, but this is a collection of class notes taken by his students, who, like all good med students of the time, studied in Latin. The rest of the best work from and on Paracelsus is in German, as far as I can tell, with few exceptions. This is a source of irritation for this monolingual Anglophone. ↩

-

Ok, Paracelsus wasn’t bearded. But he should have been. I mean, look.

↩

↩ -

Palliative care is all about helping people feel better when their disease or the treatment for it makes them feel crappy, physically and emotionally. Palliative care providers also know the legal system and end-of-life decision-making inside and out, and much of their work is counseling with worried and blindsided families who are trying to make decisions with and for their critically ill loved one. ↩

-

On the pronunciation: if you want to sound more Italian, then “soh-la dose-ees fa-cheet ven-ay-noom.” If you want to have fun in a different way, make the “c” in “facit” a hard “k” and throw in a comma and some emphasis: “soh-la dos-ees, fa-keet ven-ay-noom.” Go ahead. Try it out loud. ↩

Twitter Facebook Google+